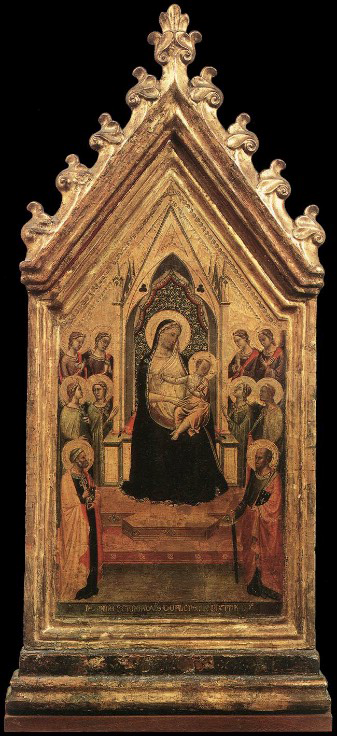

This pyramid-shaped panel of poplar wood is painted in tempera. This is a technique of binding pigments with egg yolk, characteristic of Tuscan production in the 13th and 14th centuries. The painting is enhanced with gold leaf for the background of the composition and some details. The “golden backgrounds” are directly inherited from the Byzantine artistic tradition. Particularly present in the 13th century, after the crusades which brought a large number of oriental works to Italy, the “maniera greca”, testifying to the immense impact of Byzantine painting on the renewal of Western painting, continued until the end of the 14th century when a desire for naturalism led artists to focus on the depiction of figures and landscape. This golden background lends a deeply divine character to the composition. In the centre is a majestic architectural throne, which follows the shape of the painting, set on a paved floor and decorated with geometric patterns.

The Virgin sits on this throne, represented as Maestà, that is, Virgin in Majesty. A deep interest is given to her maternal attitude. Indeed, the Mother of God holds her divine Child in her arms, sitting on her lap, with great gentleness. She is dressed in a beautiful red dress and covered with the traditional blue mantle, from her head to her feet, in which she tenderly wraps Christ. The Child Jesus makes a sign of blessing with his right hand and holds a red carnation in his left hand. According to legend, this flower was born from the tears of the Virgin Mary falling at the foot of the cross of the dead Christ. This floral attribute thus has a double meaning, on the one hand it is the symbol of the maternal suffering experienced by the Virgin, and on the other, its red colour is a prefiguration of the future suffering of Christ and his sacrifice for humanity. The divine nature of this flower is underlined by the etymology of its Greek name, Dianthus, a combination of the words Dios (God) and anthos (flower).

The throne is flanked on either side by two pairs of haloed angels, while in the foreground are two saints. On the left, St. Peter holds firmly his main attribute as guardian of Paradise, a key, which is a reference to the sentence pronounced by Christ according to the Gospel of St. Matthew (16. 19): “I will give you the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven”. On the other side of the throne, Saint Paul faces him. He holds the sword of his martyrdom in his right hand. The two saints carry carefully bound books.

Only the Virgin, whose role as intercessor between heaven and earth has a protective value, looks towards the faithful. His deep and benevolent gaze accompanies the believer in his prayer. On the other hand, as in Giotto’s and Duccio’s Maestà, kept in the Uffizi’s Maestà room in Florence, the angels and saints are not looking at the viewer but at the Virgin and her divine son The painting is done from the point of view of the believer. Therefore, the worshipper is invited to follow the example of the people depicted, and to imitate the trajectory of their gaze. The believer looks at the image of God and not the other way around. This practice of assimilating the believer to saints is characteristic of the Late Middle Ages. It is more widely known as Imitatio Christi, i.e. imitation of the life of Christ, and by extension, of the life of holy figures, whose cult is particularly widespread at this time because of their accessibility as models.

This introspective and personal work is part of a larger movement of private devotion, growing in the fourteenth century, of which our work is an excellent example, art being a primordial medium for the diffusion of domestic piety. The choice of figures depicted is typical of the central panels of triptychs, used as an “aid to prayer”. Moreover, its small size confirms the hypothesis that it was a devotional object for the laity, comparable in its use to a liturgical book such as a Book of Hours or a missal.

Although still imbued with a strong medieval heritage, notably in the use of the gold background and the massive throne of the Virgin, our work already bears witness to the nascent Renaissance of the 13th and 14th centuries, more commonly known as “primitive”. The artists are gradually trying to detach themselves from the pictorial tradition in order to give their production a more “real” value. They heralded a new plastic trend, the materialisation of Humanism, seeking to offer figures with a new realism, less symbolic, which Christianity imbibed in order to get closer to the faithful. The faces of our eight characters, with their fine and gentle features, deeply humanised, as well as the virtuosity and plastic inventiveness of the painter, are therefore completely in line with the production of primitive artists in Tuscany in the 14th century, and in particular with the Florentine artist Bernardo Daddi.

Bernardo Daddi, Virgin and Child, 1334, tempera, 56×26 cm, Uffizi, Florence