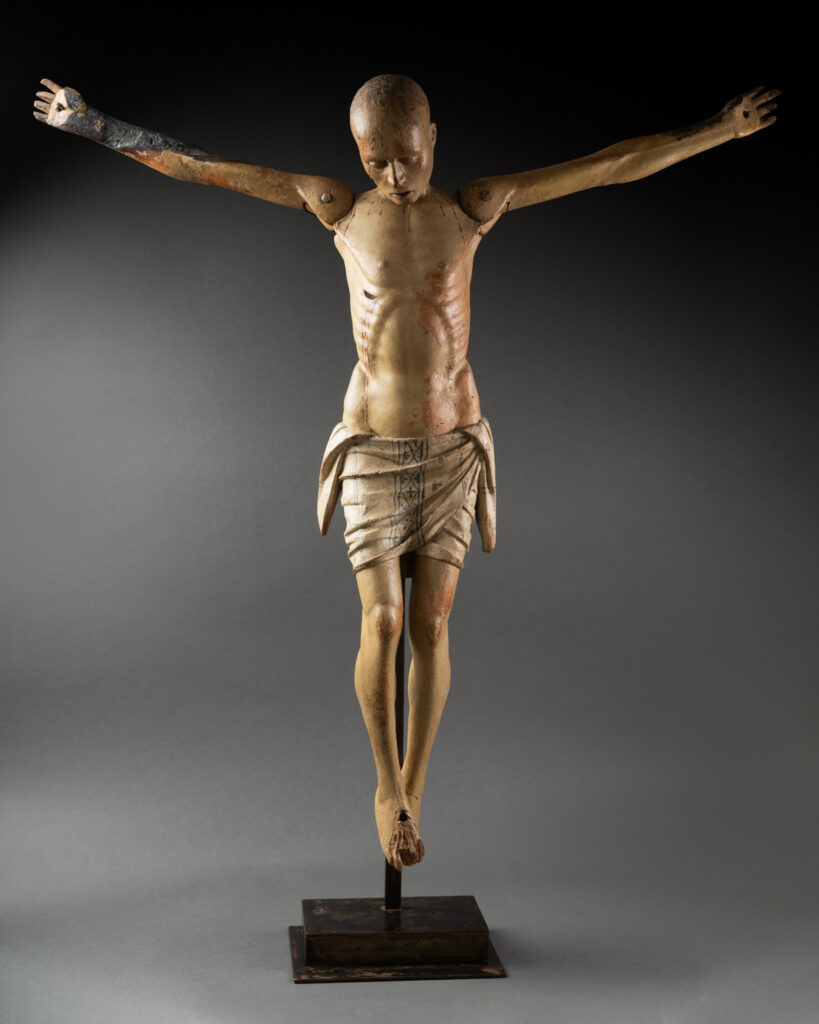

A rare beauty, this polychrome wooden sculpture depicts Christ on the Cross in a representation imbued with emotional naturalism. It dates from the 16th century and is believed to have come from a workshop in Milan, Lombardy.

He is shown with a thin, suffering head in which his obvious pain remains contained, with a slightly wrinkled forehead and a tense jaw showing the torment that inhabits him. His half-open mouth suggests the last breaths he utters before dying. Both cheeks are hollowed out, with prominent, high cheekbones, while his carefully sculpted, half-closed eyes lend a masterly dramatic tension. The end of her face ends in a pointed chin that slides slightly forward. Her slightly tilted head, which falls lifelessly, accentuates the naturalism afforded to her.

His emaciated body reveals the tendons of his arms and legs folded in on themselves. On his protruding ribcage, we can make out his open wound and tense abdomen. Christ wears a perizonium on his hips. It is held in place by a knot on each side, which emerges at waist level. Pleated fabric covers half his thighs. The end of his legs are curved forward and his feet are superimposed one on top of the other. The absence of hair and beard, revealing a bare head, suggests that it was probably originally adorned with real hair or horsehair, as was common practice at the time.

The articulated nature of this work gives it an exceptional singularity. Today, only around sixty examples exist, most of which are still in Italy. Its movable head and arms allow the Crucified figure to be transformed into a posed Christ, with his arms along his body, giving him the impression of being an ImagoPietatis. The latter is in an excellent state of preservation, with only a few missing parts to his fingers and a burn mark on his right arm, probably caused by a candle. This discreet mark echoes the rites and devotional uses to which the sculpture has been put over time. Its size suggests that it was intended for private devotion.

This type of sculpture stems from a tradition that developed in the Middle Ages during the 10th-11th centuries for popular devotion. Often linked to religious brotherhoods, they were used in the dramatised ceremonies of Holy Week. The use of polychrome wood allowed for a naturalistic representation that made Christ more human to the faithful, so that they could identify with him and share in his sacrifice. This Christ no longer simply recreates the dramatic moment of his Passion, but becomes a mediating medium for the faithful. In this way, the faithful are no longer simply spectators, but actors, with an unprecedented level of emotional involvement during the liturgy.

This sculpture can be attributed to Giovanni Angelo Del Maino, the greatest Renaissance woodcarver of the Duchy of Milan. He produced a magnificent crucifix around 1505-1530 that bears many similarities to ours. Both works are part of the Lombard tradition of religious statuary in polychrome wood, which was particularly vibrant at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. The Articulated Christ by Giovanni Angelo Del Maino is the pinnacle of this production, in terms of both the quality of its execution and its expressive intensity.

One of the most notable similarities between the two works is their articulated nature. Stylistically, the two Christs reveal a strong commitment to naturalism: the emaciated faces and anatomy reflect a desire to make Christ’s physical and spiritual suffering perceptible. Giovanni Angelo Del Maino, in particular, excelled at combining restrained expressivity with formal mastery, giving his works a subtle balance between pathos and sacred nobility, which is what we find in our sculpture. In both cases, we also note the absence of hair and beard, reinforcing their similarities. The drapery, with its dynamic folds, also illustrates a naturalistic treatment of the fabric, reinforcing the illusion of movement and material verisimilitude.

Many other artists tried their hand at these articulated Christs, and one of the best-known examples is currently on display at the Met in New York. It features the same characteristics: articulated arms, a bare head and chin, and a perizonium surrounding Christ’s hips.

This articulated Christ bears witness to exceptional craftsmanship, combining technical mastery, restrained expressiveness and spiritual intensity. Through its naturalism and liturgical function, it embodies a form of devotion that is both incarnate and participatory. A rare and precious work, it follows in the footsteps of the greatest Lombard masters, and powerfully evokes the intimate link between art, faith and emotion.